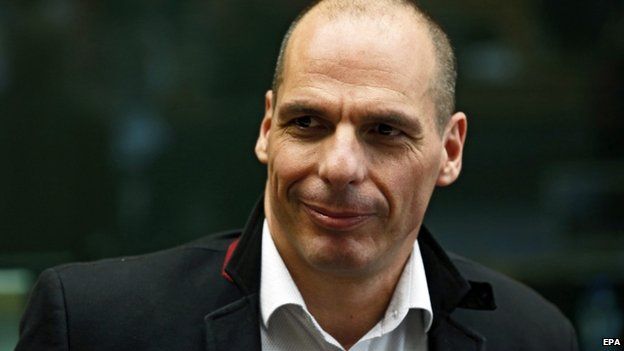

His exit raises questions that go far beyond Greece, to the heart of Europe's future, so naturally I wanted a word.A few hours after his surprise resignation, I chanced upon Yanis Varoufakis sitting in a cafe surrounded by friends.

A minder gently interposed himself. I reminded the ex-finance minister that I'd interviewed him recently, so he politely shook my hand, saying he wasn't doing any interviews and wanted a break from all that.

He added that it was good to be able to have a beer at lunchtime. But he made it clear he still had a role as an MP. He wasn't going away.

I bet he isn't. He is still a huge international celebrity with all the clout that brings.

During this brief and trivial conversation, I was entranced not only by his warm smile and engaging gaze, but by the vibrant deep blue of his shirt and its subtly rounded black squares.

I wondered where he had bought it. Not that it would fit me. Mr Varoufakis, unlike your humble correspondent, is a fitness fanatic and a hunk.

The Essex University-educated Marxist economics professor is in political terms, a rock star. He famously wears a leather jacket, but never a suit and tie. He rides a motorbike rather than take a ministerial car. He oozes charm and charisma.

No wonder the other leaders can't stand him.

Half the world has a crush on Mr Varoufakis. The other half would simply like to see him crushed, and perhaps he has been.

You can argue about his intrinsic merits, but his appeal tells you several important things about politics at home and abroad. On one level, it is fairly simple.

My 17-year-old daughter is one of Mr Varoufakis's fans. It is not the Marxist economics. The looks have something to do with it.

Pecs appeal

But before she saw any pictures, she heard him on the radio - and for the first time ever she showed an interest in one the politicians who provide the soundtrack to our lives on BBC Radio 4.

His words seemed fresh - his directness, his ability to engage with the question - and, impressively in a foreign language, to use language both precisely and playfully.

It should be obvious by now, to everyone but mainstream politicians themselves, that there is a hankering for authenticity.

Evasive carefully crafted non-answers are expected and scorned. Those who both talk straight and are ready to exploit their own personality, rather than retool it by focus group, score well.

I am thinking Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson, Chris Christie - and none of them have Mr V's pecs. But it goes deeper than that.

Who is Yanis Varoufakis?

- born 24 March 1961 in Palaio Faliro, Greece

- parents heavily involved with politics, particularly the Panhellenic Socialist Movement

- changed the spelling of name from Yannis to Yanis at school

- studied economics at the University of Essex, then an MSc at Birmingham University and then a Phd back at Essex

- taught at many academic institutions and has written several books on game theory

- adviser to George Papandreou's government (2004-06)

- appointed finance minister by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras on 25 January

- resigned 6 July

On my last evening in Athens, I went for a quiet kebab in a side street in a working-class area. The owner, who has had a cafe for 10 years and opened this little joint three years ago, was eager to talk politics.

He said Syriza was "an experiment" and Mr Varoufakis a rarity - he said what he meant and stuck to it.

That was a good thing - but meant he had to go. He was not really a politician - he was too straight - most of them had to be a little crooked. He did not mean corrupt - he meant they took the less-than-direct path, leading to deals and compromises.

One close observer of the Greek crisis and Syriza, Paul Mason of Channel 4 News, makes exactly this point in his engaging blog, adding the party is changing. How Mr Varoufakis responds to any deal, any imposition of austerity, will be worth watching.

'Cretan character'

The man behind the check-in desk at the airport also wanted to talk politics. "It's because he's from Crete," he said of Mr Varoufakis. "Strong," he said, raising his clenched fists, "stubborn."

Many of Syriza's supporters will see stubborn Yanis as the single victim of a failed coup.

One Greek minister, George Katrougalos,told me: "Some political circles in Europe are afraid that we may prove that there is an alternative to this orthodoxy of neoliberalism, because we are going to have elections in Spain, Portugal and Ireland.

"What if we had success here in Greece? That would clearly be seen as a bad example."

It is true the first democratically elected government of the hard left in Europe in my lifetime, believes in the sort of economics specifically rejected by the rules of the European Union.

The car crash we are seeing now is not an accident - it is the result of neither side wanting to move out of the road.

The Greek government fundamentally sees the EU as a capitalist club, with rules designed to benefit the rich, the bankers and big business. They want to break that. Critics say they want to emulate Venezuela.

The stunning victory of Syriza in January was a big moment for the left, and the next few days are even more important.

Whether the Greek government wins or loses, stays in the EU or is chucked out, is vitally important for other newly minted hard-left parties in Europe.

The minister is right - Tempo de Avancar in Portugal and Podemos in Spain will be watching and drawing lessons.

The danger for the EU is that the supporters of the hard left decide that staying in turns the old leftist slogan on its head and: "The people united, will always be defeated."

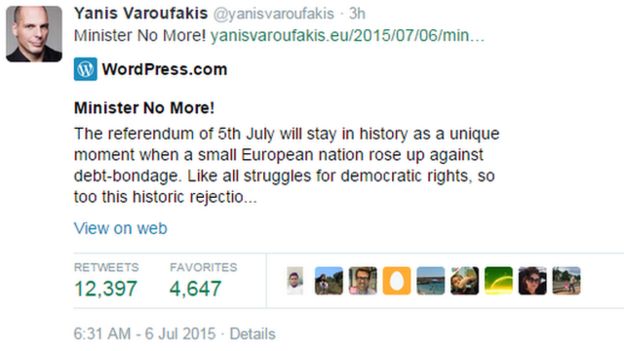

But the meaning of Mr Varoufakis's exit after a popular vote goes even beyond the call to redesign the nature of the European Union's economic fundamentals.

It is about democracy in the European Union. The relationship between what individual states want and the collective will of those joined in federation, or nation or organisation, is no simple thing.

It is a vital question stretching way back into the past and is certainly worth another article.

But Mr Varoufakis, accused of naivety and childishly sticking to his guns, believed that the election of Syriza back in January, and this referendum, was a clear mandate to abolish austerity.

The other members of the eurozone disagree.

Mr Cameron's mandate is less clear and less precise, and he is not the sort to offensively flaunt stylish menswear or toned muscles.

But he might want reflect not only that that confrontation appears to be against the club rules, but that all the other prime ministers and presidents around the table have a mandate too.

Mr Varoufakis has exited stage left. Greece may follow.

As often in a drama, the shocking killing off of a central character throws into stark relief the uncertain denouement of an unfolding story

No comments:

Post a Comment